Microbiome: The world within

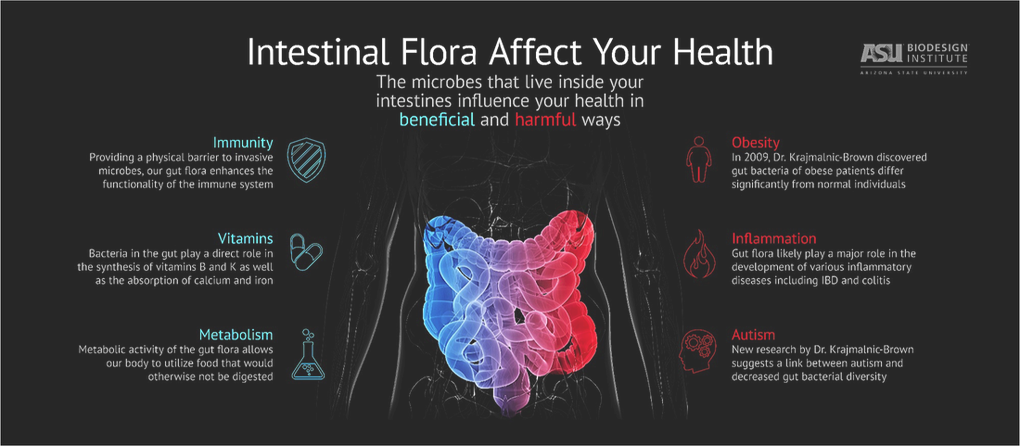

This new and fascinating field of study into the human microbiome is revealing the depth and interconnected-ness we have with the many different types of organisms which keep us alive. We are a small universe within, dependent on the health and vitality of our inner ecosystems. Current estimates put the number of microbes roughly matching the number of human cells in your body! From the digestion of foods to immune system functions to directly influencing our brain chemistry. As more studies are done and more amazing findings are shared we are starting to get the picture that you can not be a healthy individual unless you have a healthy community of microbes. This changes how we need to look at ourselves and how we treat illness. Some disease seems to be rooted in the imbalance of the flora and fauna of our digestive tracts, and new treatments are emerging.

Understanding what is going on in our bodies is the first step in learning how to influence and optimize our systems. Probiotics and Prebiotics are popular and mainstream with good results from even minor interventions.

Understanding what is going on in our bodies is the first step in learning how to influence and optimize our systems. Probiotics and Prebiotics are popular and mainstream with good results from even minor interventions.

Wikipedia says:

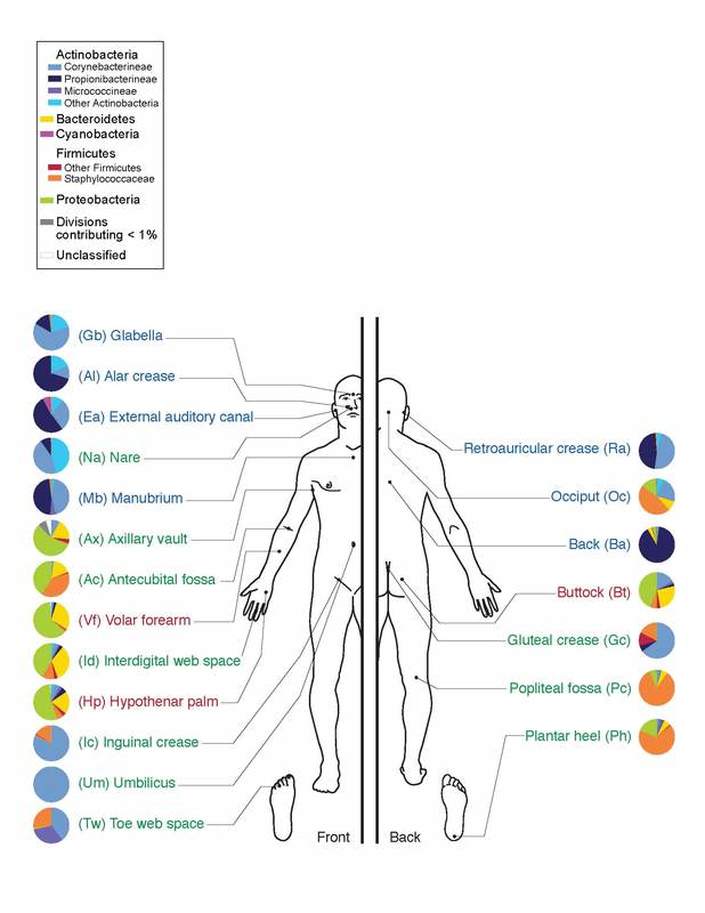

The human microbiota is the aggregate of microorganisms that resides on or within any of a number of human tissues and biofluids, including the skin, mammary glands, placenta, seminal fluid, uterus, ovarian follicles, lung, saliva, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, biliary and gastrointestinal tracts. They include bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses (bacteriophages). Though micro-animals also live on the human body, they are typically excluded from this definition. The human microbiome refers specifically to the collective genomes of resident microorganisms.

Humans are colonized by many microorganisms; the traditional estimate is that the average human body is inhabited by ten times as many non-human cells as human cells, but more recent estimates have lowered that ratio to 3:1 or even to approximately the same number. Some microbiota that colonize humans are commensal, meaning they co-exist without harming humans; others have a mutualistic relationship with their human hosts. Conversely, some non-pathogenic microbiota can harm human hosts via the metabolites they produce, like trimethylamine. Certain microbiota perform tasks that are known to be useful to the human host; but the role of most resident microorganisms is not well understood. Those that are expected to be present, and that under normal circumstances do not cause disease, are sometimes deemed normal flora or normal microbiota.

The Human Microbiome Project took on the project of sequencing the genome of the human microbiota, focusing particularly on the microbiota that normally inhabit the skin, mouth, nose, digestive tract, and vagina. It reached a milestone in 2012 when it published its initial results.

The human microbiota is the aggregate of microorganisms that resides on or within any of a number of human tissues and biofluids, including the skin, mammary glands, placenta, seminal fluid, uterus, ovarian follicles, lung, saliva, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, biliary and gastrointestinal tracts. They include bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses (bacteriophages). Though micro-animals also live on the human body, they are typically excluded from this definition. The human microbiome refers specifically to the collective genomes of resident microorganisms.

Humans are colonized by many microorganisms; the traditional estimate is that the average human body is inhabited by ten times as many non-human cells as human cells, but more recent estimates have lowered that ratio to 3:1 or even to approximately the same number. Some microbiota that colonize humans are commensal, meaning they co-exist without harming humans; others have a mutualistic relationship with their human hosts. Conversely, some non-pathogenic microbiota can harm human hosts via the metabolites they produce, like trimethylamine. Certain microbiota perform tasks that are known to be useful to the human host; but the role of most resident microorganisms is not well understood. Those that are expected to be present, and that under normal circumstances do not cause disease, are sometimes deemed normal flora or normal microbiota.

The Human Microbiome Project took on the project of sequencing the genome of the human microbiota, focusing particularly on the microbiota that normally inhabit the skin, mouth, nose, digestive tract, and vagina. It reached a milestone in 2012 when it published its initial results.